‘I Trafficked Women at a Famous Hong Kong Nightclub’

Image Caption: Mary Zardilla, a former mamasan at Club Bboss. Photo: Sylvia Yu

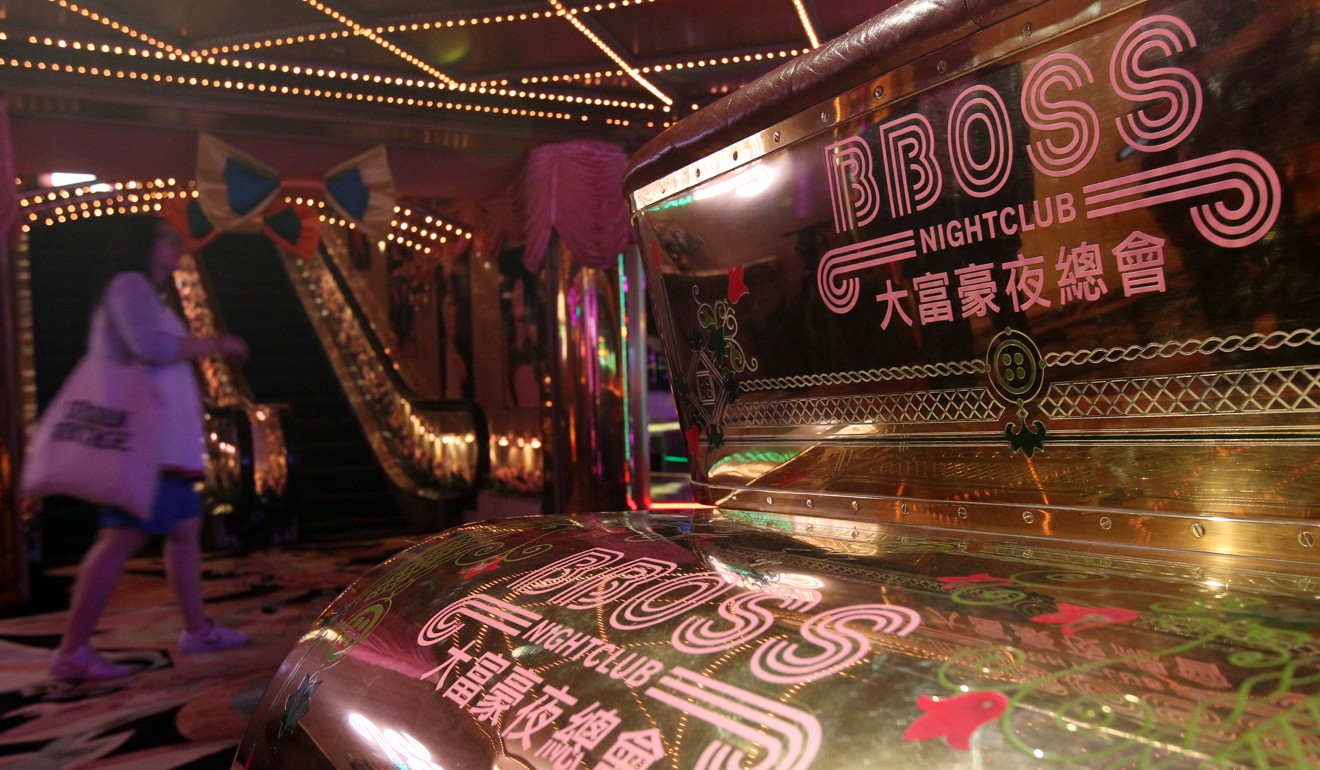

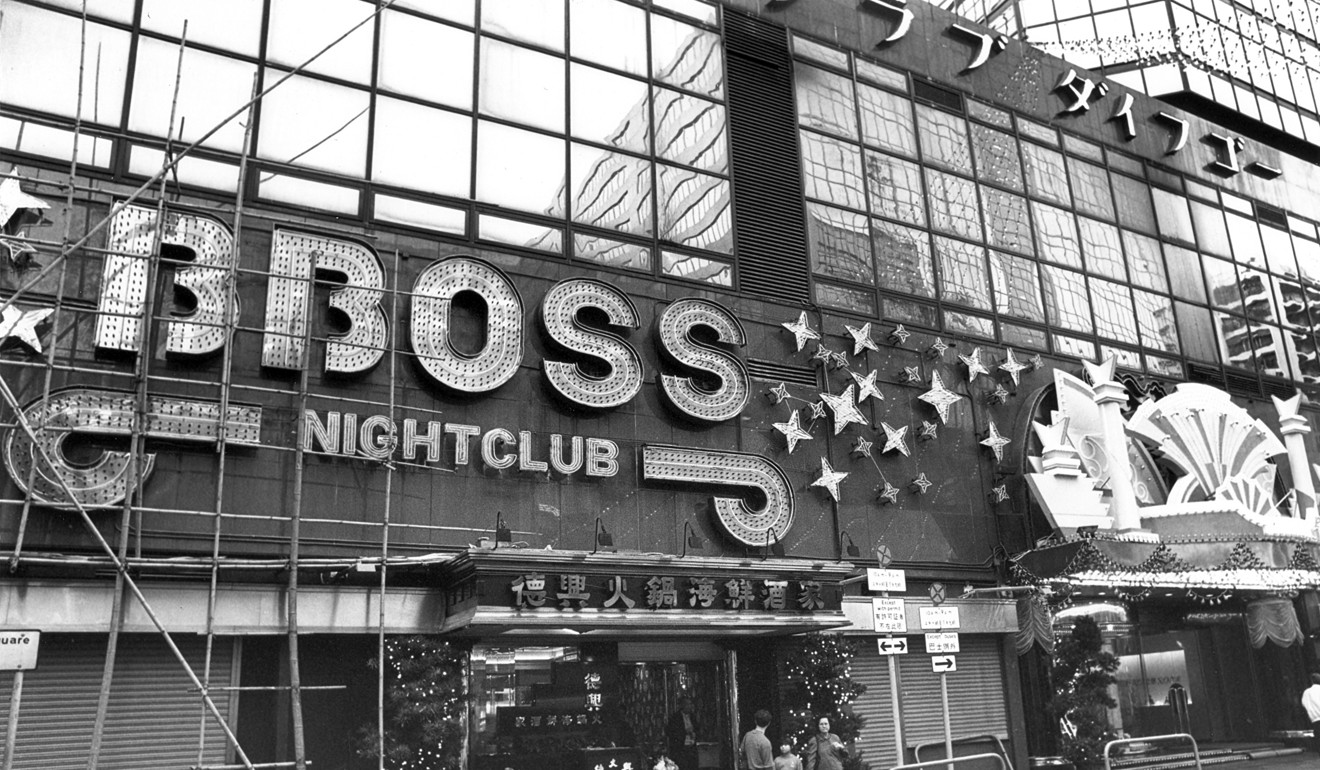

Mary Zardilla looked like she had it all. It was 1986, the heyday of Hong Kong hedonism and she had spent the past decade climbing the greasy pole of the entertainment business to its gaudy, gold-plated zenith – the self-appointed greatest night club of them all, Club Bboss.

Like many others, Mary had risked much to be here, lured by the promise of rubbing shoulders with the movers and shakers of the day. The club’s clientele was a veritable “who’s who” of 1980s Hong Kong. Celebrities, politicians, famous businessmen… all were common sights at this Tsim Sha Tsui landmark, a 70,000 sq ft nightclub-cum-amusement park for men that boasted bright lights, lavish floor shows and more than 1,000 perfectly coiffed hostesses.

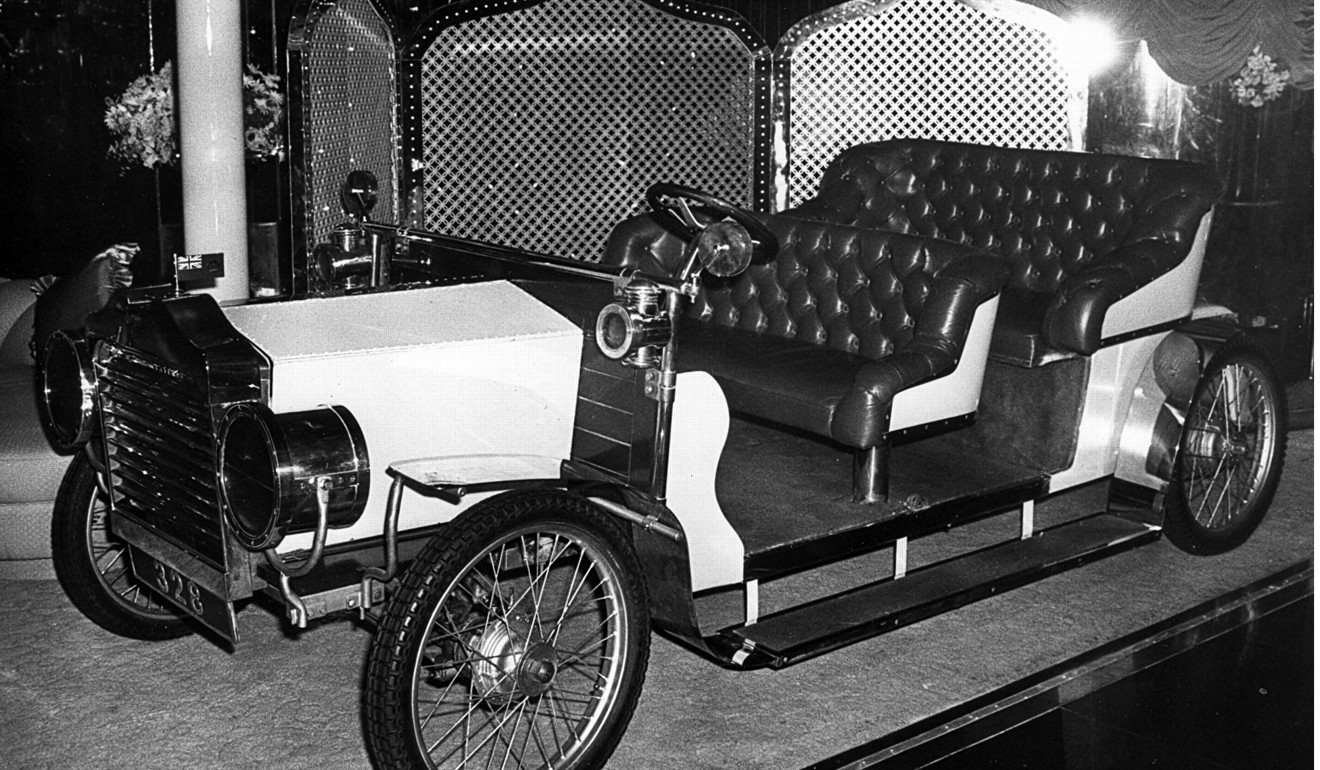

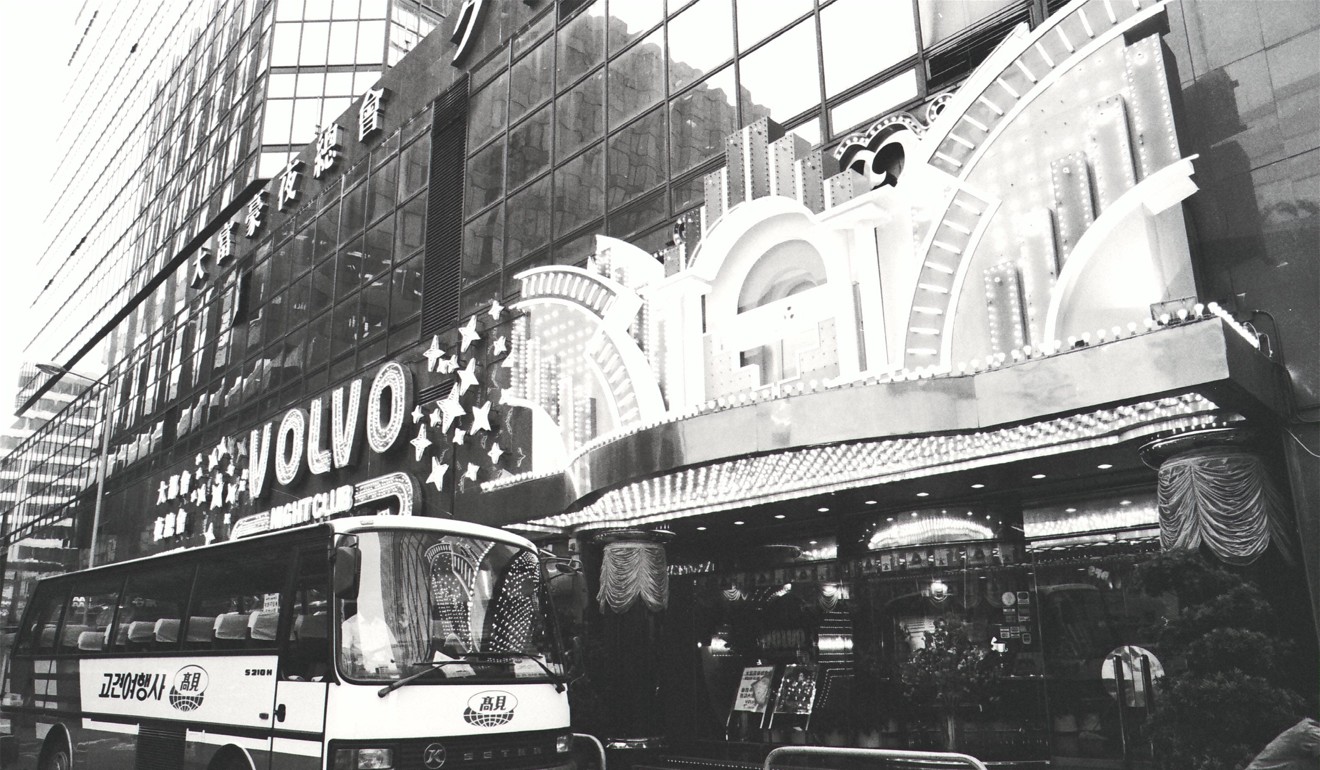

As one of the city’s last Japanese super clubs, Club Bboss – formerly Club Volvo – was about nothing if not conspicuous consumption. The rich and famous would arrive at the curbside in their Rolls-Royces, only to be ferried to their booths in gold-plated golf carts designed to look like the vehicles they had just left.

And once inside they might meet one of those many perfectly coiffed hostesses – but not before first encountering someone like Mary.

Mary was one of the club’s foremost mamasans. Her job was to match up the club’s male clientele with one of the 100 or so escorts under her control – and it was a job Mary, who learned Japanese for the role, was particularly good at, having acquired an uncanny knack for reading men’s minds when it came to their tastes in women.

So good, in fact, that the club gave her two armed bodyguards as round-the-clock protection when she joined from a rival establishment – a skilled mamasan like Mary could bring in a lot of money for a club, many of which were run by triad gangs, and employers did not take kindly to being abandoned.

“Some mamasans got beaten and hospitalised to warn you against leaving [for another club],” recalls Mary, now 63, petite with a pretty, wrinkle-free face that makes her look decades younger than she is. “[When I left my former job], I said, ‘please don’t hurt me. I served my contract. I have to support my poor family in the Philippines’.”

‘I WAS A TRAFFICKER OF WOMEN’

Luckily for her, Mary was allowed to leave for Club Bboss, where she worked alongside mamasans from Australia, Japan, China and Korea, managing girls who, like her, had begun working there voluntarily, out of financial need driven by their impoverished family backgrounds.

“We were trapped with no other options,” says Mary, who herself began working at 16 to support her parents and siblings.

As a pimp, Mary mentored her girls in everything from etiquette to styling. Every night she introduced them to “johns” who were charged fees by 15 minute increments. Johns were charged by the club anywhere from HK$1,900 to HK$3,500 or more per encounter, depending on how wealthy they appeared.

Technically, Mary’s work – and that of her girls – was entirely legal, but Mary herself is in little doubt as to what her role constituted. “I sold girls. As a mamasan, I trafficked girls,” Mary now says, bluntly.

To get around the laws on prostitution, their salaries were paid by nightclub accountants and they were taxed as hostesses – something that is considered legal work.

To keep their mamasan happy, the girls would give Mary money or gifts as a “favour”. The girls needed to do this to get an edge on their competition for the highest paying, most attractive johns. Mamasans were in charge of their own schedules and were the most powerful in the food chain. Mary had only one boss – the owner.

The link between human trafficking and the escort business is not always clear. At high-end places like Club Bboss, for example, working women arrived on their own accord from places such as Japan, America, Britain, Latin America, the Philippines and mainland China. And, of course, there were local Hongkongers, too. Many of the women from overseas had entered Hong Kong on tourist visas before applying, voluntarily, for work at one of the 10 or so top clubs. Mary says all the women were hoping a man would sweep them off their feet like Richard Gere in the film Pretty Woman.

“The girls can make more money in clubs than brothels. Brothels are faster turnover, but they are more controlled. Nightclubs give more freedom and pay more,” she says.

At the lower-end establishments, however, it’s less clear how much choice the women had. Mary knew many clubs that recruited women from overseas, paying for their plane tickets and all expenses, but did not allow them to leave the premises after they arrived.

In some of the worst cases, women were clearly trafficked. One of Mary’s girls at Club Bboss, Isabelle, had been trafficked from Manila by a triad gang who had deceived her about the type of work she would be doing in Hong Kong. When she arrived, the gang forced her into prostitution in a private home. Isabelle was forced to sleep with up to 30 men a night, with the triads charging HK$50 per john. A man guarded her at all times to prevent her from escaping. Isabelle’s bodyguard later bought her from her owner after the pair formed a bond and they ended up getting married. Yet, even liberated, with limited options for income, Isabelle found herself back in a similar line of work as one of Mary’s hostesses, albeit with more freedom and pay.

And even for those women who had entered the field voluntarily, by the time they realised Richard Gere would not be coming to save them, it was too late. “Some girls wanted to find a better job. But unfortunately they hadn’t finished school or didn’t have skills,” Mary explains. “Freelancers can leave anytime they want… but don’t have other options and they end up trapped.”

THE DESCENT

The descent into pimping women happened slowly for Mary. At 16, she had dropped out of school and started working in a factory to support her parents and seven siblings. Her father died three years later leaving her mother, a laundry woman, devastated. Mary stepped up as the eldest daughter to support the family. Mary left the factory job to join a cultural dance troupe and the troupe took her to Hong Kong in 1972. During the troupe’s tour, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law back in the Philippines, prompting Mary and other dancers to search for more permanent work in the city.

That year, she met a Filipino man working in entertainment and married him a few years later. He cheated on her frequently. Pained, she focused on making money to send back to her family. “I longed for love. I didn’t have love, I became a slave to money,” she recalls.

She applied for a receptionist role at a club in Tsim Sha Tsui not realising it was a hostess job. “I was innocent and so deceived. Many are deceived into working as prostitutes.” But she refused to sleep with the johns and was instead groomed as a mamasan.

Unacquainted with this underworld, she had no idea what mamasans did nor what big money they made. She learned on the go. “I was entertaining customers like a public relations person. I studied Japanese and became good. I would ask them what kind of girls they preferred. I soon learned Japanese businessmen like young girls.”

The money hardened her. Her starting salary was HK$20,000 a month plus commissions and she got HK$15,000 as a one-off payment for signing her contract. But she found out that other mamasans were being paid HK$30,000 a month and HK$20,000 for signing a contract, so she asked for a raise. The raises were never enough so she began climbing the ranks of the leading clubs before finally rising to the top – Club Bboss, where she was paid HK$500,000 annually and HK$80,000 for signing her contract.

She was not the only one lured by the promise of riches. “We charged HK$1,000 for sex in the 1980s,” she says. “Back then [many of the Hong Kong Chinese] girls were married. They, too, were lured by the money.”

Clients gave her girls jewellery, money to buy land, houses and apartments back in their home countries. At times, Mary was given blank cheques by the clients. She had several wealthy boyfriends on the side. Some of the girls became savvy at buying and selling real estate and left the club with small fortunes. They were regularly paid to attend parties with high-profile Hong Kong businessmen. “They were high-end call girls, dressed so elegantly,” says Mary.

Yet even then, at the zenith of her profession, surrounded by the rich and famous and able, seemingly, to pluck money from thin air, Mary knew that deep inside she and her girls were suffering and lost. Amid the stream of glamorous clients, Rolls-Royces and golden golf carts, the women battled drug addictions, alcoholism and ever-creeping levels of self-loathing and emptiness.

“While working in the club, we didn’t have a life. It’s so temporal… nice restaurants, fancy clothes, all temporary happiness. Any prostitute who says they’re happy, they’re in denial. The girls would go back and cry even if they had made US$10,000 that night with a man from the Middle East. You’re forced to make love with a man you don’t like. Your soul and emotions have to be numb. Only drugs numb.”

Then there was the sexual abuse and exploitation, which was widespread. One time, a client strangled one of her girls.

TROUBLE WITH THE LAW

The escort business operates in a shady area, where the line between what is legal and what is not is not always clear. Mary says clubs would often be tipped off about police raids before they happened – “corruption is everywhere”. The mamasans and women feared the police. Mary feels that had more police been trained to identify women in the red light district who felt they had been coerced into prostitution, some lives could have been saved. “The police must have a deeper understanding that these women are trapped and that in their heart of hearts, these women hate their work. No one wants to be a prostitute.”

A Hong Kong police spokesperson said they had found prostitutes from the Chinese mainland, Southeast Asia, Europe and South America who had been trafficked to Hong Kong on tourist visas. However, these women, according to the police, are usually reluctant to speak out.

Last year, police arrested 266 people on suspicion of keeping a vice establishment. In Hong Kong, prostitution itself is legal, but organised prostitution is not.

While some clubs and operators from Tsim Sha Tsui have migrated to the Wan Chai bar street, the days of the luxurious nightclub scene are over – Club Bboss itself shut in 2012.

Yet even now, campaigners estimate there are anywhere between 20,000 to 100,000 children, women, and men working in prostitution in Hong Kong. According to Zi Teng, a support group, around 1 in 50 are under 18.

According to one NGO worker, some smaller nightclubs in Kowloon have forced underage Chinese girls – usually from broken families – into prostitution through debt bondage. The girls are lured by mamasans who ask if they want “easy cash” or “pocket money”. The girls soon get into debt, finding they owe their mamasans HK$10,000 to HK$20,000 for living expenses or to finance their cocaine or ketamine drug habits.

Despite such problems there is no government funding to support NGOs to provide direct intervention, according to the NGO worker.

Sandy Wong, chairperson of the Anti-Human Trafficking Committee of the Hong Kong Federation of Women Lawyers, says more needs to be done to stop the demand for prostitution. “In Sweden, targeting the sex buyers helps reduce prostitution and sex trafficking significantly and it is a model increasingly adopted by other countries. It is a model we should adopt in Hong Kong.”

TRANSFORMATION

Every night, Mary and her girls drank to ease the pain. Their daily routine before their work would involve lunch then a beauty parlour session. In 1991, a friend who owned a beauty clinic in Cebu visited Mary to ask for her help setting up another business in Hong Kong.

Mary admitted she was a mamasan, but rather than judge her, the friend, a Christian, told Mary that Jesus came to save the sinners, tax collectors and prostitutes.

The friend offered to study the Bible with Mary. “All of a sudden something pinched my heart,” recalls Mary. “But I was a millionaire. I was afraid to say no. I was afraid of getting cursed by God and that I’d lose my money.”

As she prayed, she felt cleansed for the first time. But she continued to struggle with guilt and shame.

What sealed her conversion was seeing her young nephew, who had been dying from cancer, healed after another friend, Rita, prayed for him.

This convinced Mary there must be a higher power and she invited Rita to Hong Kong to speak with her girls, hoping for more miracles.

For the next month and a half, they conducted Bible studies every day. Around 10 girls “experienced a new hope and the power of God and the girls were healed of their emotional pain, anger, depression, drug addictions and alcoholism”.

“All of a sudden their countenance changed, their attitudes and characters changed. They had so much hunger to learn about the Christian faith.”

Mary began to use the karaoke bar she owned as a meeting place for the women to learn about their new faith during the day. At night it continued to function as a bar for prostitution.

One by one the girls quit their work, as did Mary – after 17 years in the business, she paid her boss HK$200,000 so she could leave. “I knew it was time to quit because of my conviction. I felt so bad and couldn’t walk into the club. I didn’t care if I didn’t have money or a job.”

The next year, she sold her bar and moved back to the Philippines.

PEACE OF MIND

Back in the Philippines, Mary worked at restoring her marriage, which is now strong. Over the years, she has mentored many women and recounts her past in public speeches. Recently, her testimony at a Hong Kong church moved a congregation of domestic helpers to tears. Now Mary wants to tell as many mamasans and bar girls as she can that there is hope. “I want to tell them they’re not stuck,” she says, tearing up. She is still in touch with six of her girls who left the world of prostitution. They are now working as dishwashers, or cleaners. One is a restaurant floor manager.

“We may not have luxury but we have peace and joy. There’s no oppression,” she says. “Our identity is restored: money can’t buy that.” ■

Mary’s name has been changed to protect her identity

(Source: SCMP.com)