Sacrifice of Leaving Child Behind Laid Bare in British Filmmaker’s the Helper Documentary About Hong Kong’s Foreign Domestic Workers

Seeing hundreds of thousands of helpers on the streets of Hong Kong inspired Joanna Bowers to make a film about the maternal sacrifice many make to work overseas

More than 300,000 domestic workers, predominantly from the Philippines and Indonesia, live in their employers’ homes in Hong Kong.

These helpers clean, cook and look after children for a minimum wage of HK$4,410 per month, most of which they send back home to support their families. The amount may seem meagre to many Hong Kong residents, but it is more than most of the helpers would earn in their home countries.

By employing a domestic worker, often both adults in the family can commit to full-time jobs, increasing their household income.

When British filmmaker Joanna Bowers moved to Hong Kong six years ago from Los Angeles, she saw the helpers on their Sunday day off for the first time and decided their stories needed to be told.

Bowers raised just under HK$700,000 in 30 days through an online donation campaign which helped fund The Helper documentary. It premiered in May and will be shown at AMC Pacific Place cinema from this week.

The film follows the daily lives of five foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong.

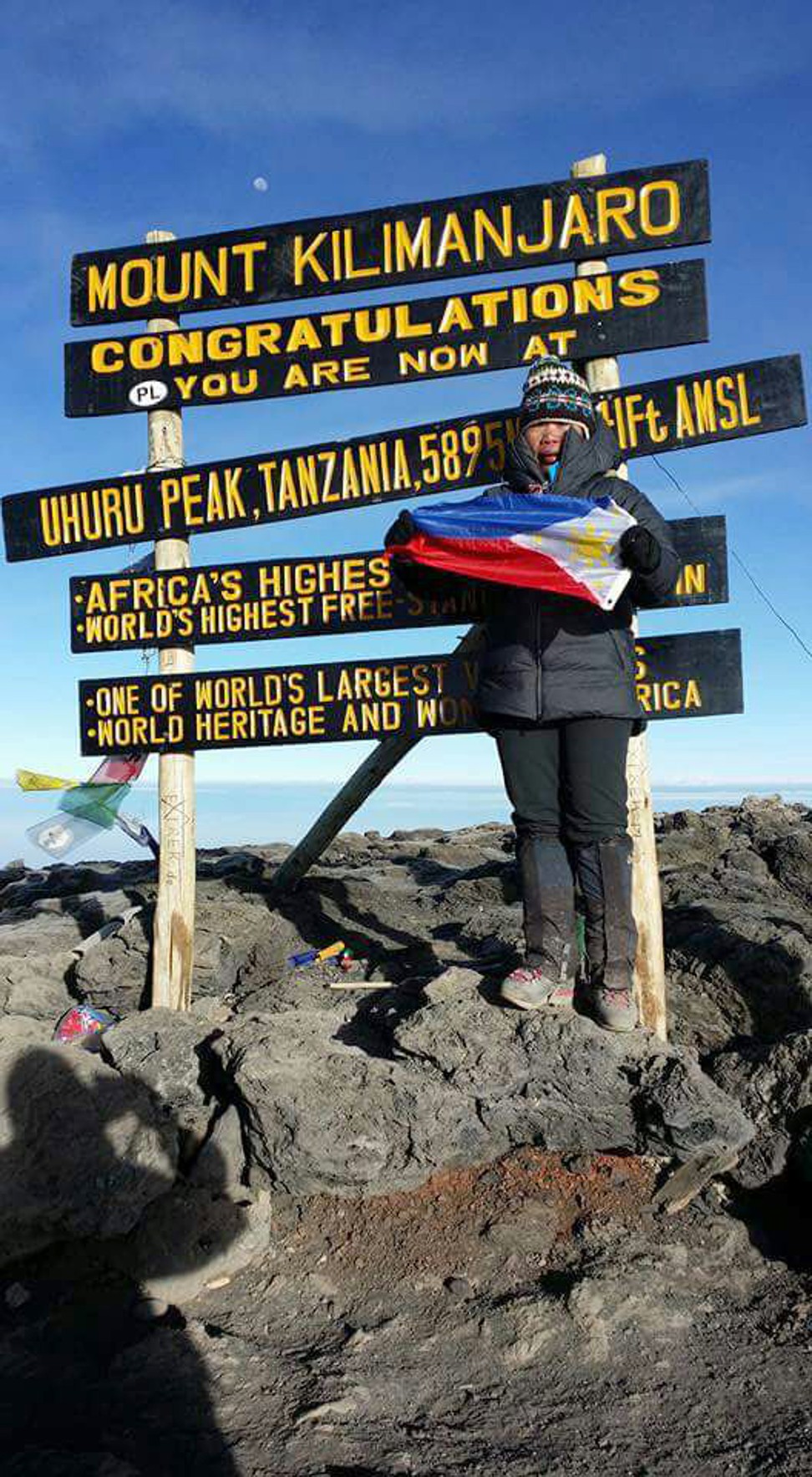

One is Liza Avelino, a 46-year-old Filipino who climbed Mount Kilimanjaro, in Tanzania, in August, in aid of the charity Help for Domestic Workers. Also featured in the documentary are the Unsung Heroes, a local choir made up of helpers, who have performed at Hong Kong’s annual Clockenflap music festival.

Watch: Joanna Bowers shares her thoughts on the film

Bowers graduated from the University of Leeds in Britain with a degree in broadcast journalism before moving to Dubai for a year. She then worked in Los Angeles for the next 11 years where she set up her own company, Cheeky Monkey Productions. Since moving to Hong Kong she has given birth to a daughter, Jemima, and said becoming a mother had made her appreciate even more the maternal sacrifice of domestic workers, who leave their children behind in the hope of ultimately giving them a better future.

What was the inspiration behind The Helper documentary?

I remember my first weekend in Hong Kong, walking around the walkways in Central on a Sunday and seeing the hundreds of thousands of women sat out there, not integrated into society. I got to thinking that these women look happy. Even though they are sitting in a cardboard box, they are having a great time, they are socialising and sharing food. I looked and thought; there is a reason behind this.

As a filmmaker and a woman I am driven towards women’s stories. When I started to get to know a few domestic helpers in Hong Kong, all of them had incredible stories. Nobody is aware of this or understands what is behind these happy, smiling faces: a fantastic facade on what are quite often difficult circumstances. They work incredibly hard. This was an opportunity to shine a spotlight on these women and show what is behind them.

Did any of their stories in particular really stick with you?

The five-year-old daughter of one member of the Unsung Heroes choir was sexually assaulted by a neighbour back home. The worst thing is that she wasn’t able to prosecute and had to drop the case. It is a really tricky thing. We have ended up having to change some of the language in the film because she doesn’t want her daughter to just be remembered as a victim. She wants her to be able to move on with her life.

That is hard as a filmmaker: you don’t want to have a negative effect on someone’s life. But, that being said, it is such an impactful part of the film because it makes you realise how ginormous this sacrifice is. The domestic helper’s sister had been looking after her daughter and was very ill, so it put her daughter in a vulnerable situation, but being here in Hong Kong is her only option. As a mother myself now, I can’t imagine having your child at such a risk but having no other choice.

What was the most memorable moment from filming?

One of the main themes of the film is maternal sacrifice, and during the making I was pregnant with my daughter, Jemima. It was completely fine throughout most of the filming, but as we were getting towards my due date, we were also getting towards the big finale of the Unsung Heroes performance on the main stage at Clockenflap. And my due date was a week later. I was blindly optimistic, thinking of course I would be at the performance.

About four days beforehand my blood pressure shot up, so my doctor told me I was off to hospital and couldn’t leave until I had the baby. Fortunately I have an amazing team and I had given them a specific shot list. I was in the hospital room watching the Unsung Heroes live at Clockenflap in front of thousands of people, on the YouTube live stream. We were so excited. The nurse checked my blood pressure and it was through the roof. I told her the story and she was Filipino, so she stayed and watched with us.

What was the hardest part of filming?

Getting the footage of Liza Avelino going up Island Peak in Nepal was a challenge. I had just had a baby, so I wasn’t going up that mountain. We had to train her on how to use a GoPro camera, how to record audio. That was an adventure.

What do you want people to take away from the film?

I’ve always been hoping there would be some empathy and an increased understanding, even for us.

When we went to film in the Philippines, I had an assumption about what these women’s lives were like before they came to Hong Kong. But we saw the abject poverty when we were filming; we have footage of women doing the laundry in a tub behind a house in Manila, and then washing their kids in that same tub. I like to think that if someone in Hong Kong watched that, they might understand why their helper might not know how to use a washing machine. Little things like that: understanding where people have come from and understanding what their life is actually like.

Hopefully people in Hong Kong will be able to draw the parallels. A lot of domestic helpers in Hong Kong are working for families where both parents have returned to the workplace. They are returning to work to afford a better life for their children, which is the exact same thing that the domestic helper in their home is doing. Everyone is in the same boat.

How has making the documentary changed your relationships?

I make sure as much as humanly possible that I am home to put my daughter to bed. I understand that I am so fortunate to have that privilege. It definitely makes me squeeze her a little bit tighter at night.

Both my parents are teachers and I have met domestic helpers here who come from a similar working background, yet they are here in Hong Kong cleaning someone’s bathroom. I am just lucky I have a British passport. It is the understanding that by virtue of our location of birth we are afforded a lot more or a lot less.

What do you think of the culture of having domestic helpers in Hong Kong?

It’s a tricky one. They get a fraction of the living wage compared to other places in the world but when you look at the life-changing impact it can have, especially compared to the salaries they can earn back home, it is an opportunity.

I think for such a country where the women are the main breadwinners, the Philippines still seems like it is such a patriarchal society. These women are bringing in all the money and yet they are not in control. The family pressure on them is extraordinary.

We are looking into distribution of the film in the Philippines. For the Filipinos and Indonesians to see their country women up on the big screen as heroes of the film would be wonderful. There has been a constant theme of them asking why we are making a film about them – they are so baffled and surprised. They don’t see how incredible their contribution is.

Watch: how do Hong Kong’s domestic helpers sleep?

What problems do we need to overcome in Hong Kong in relation to domestic helpers?

The overwhelming answer when the women were asked if they could change things was that someone would say thank you. That is a mindset. Saying thank you is showing empathy and gratitude. We are launching an impact campaign from the film called Thanks A Million where we attempt to collect a million thank yous from around the world for domestic helpers. To make a public gesture of gratitude, we think, is a way to document a change in mindset – to count how many people we have touched.

We are also planning corporate and school screenings, for people who maybe wouldn’t have time to go to the cinema and people who are the next generation in Hong Kong growing up with helpers.

THE OTHER SIDE OF JOANNA BOWERS

What is the one iconic element that you think best represents Hong Kong?

I love the neon. It’s a shame that it seems like an art that is dying out and being replaced with LEDs. The other thing I love is the paper shops with offerings for dead ancestors – there are tennis rackets, washing machines, speed boats, private jets – amazing. And it’s another one of those crafts that is pretty unique to Hong Kong. I think it’s fascinating.

Where is your favourite place you have lived?

I loved that in Los Angeles I could go 40 minutes one way and be snowboarding in the mountains, or 40 minutes another and be at the beach in Malibu. But I love Hong Kong in a similar accessibility way. I have never travelled to so many countries in my entire life since I moved here: China, Thailand, Nepal, Indonesia, Taiwan and Sri Lanka.

I just did! In a beautiful villa on the beach in Sri Lanka with my family and friends who have flown in from all over.

Who would play you in a movie?

Gal Gadot – I’m obsessed with Wonder Woman. It was always my dream that I was going to direct the reboot of Wonder Woman.

Where is the one place you want to visit?

I want to go and get really good at playing polo on a ranch in Argentina. I played in Los Angeles and the Middle East but I am not very good.

Why did you call your production company Cheeky Monkey?

When I lived in Los Angeles and finally realised I had enough projects going on that I needed to set up an umbrella company, I wanted something quintessentially British. When I was little in England, my mum and dad used to call me cheeky monkey, partly because I was cheeky and partly because I used to sit with my feet on the tray of my high chair. So cheeky monkey stuck.

What is your favourite movie or documentary?

Something I watched that just stuck with me when I was pregnant was called Hot Girls Wanted: Turned On, made by Rashida Jones. It is about prostitution and online pornography and it broke my heart and scared me. I just had no idea that this world existed. It was one of those moments when I thought how impactful film is.

What is your favourite mother-daughter bonding activity?

Ever since she has been really small, Jemima has loved music. We have little dance parties at home – I crack the tunes and she is hilarious. She just started ballet.

(Source: SCMP.com)