Goodbye Debt: Helping Domestic Helpers Escape Modern Slavery in Hong Kong and Around the World

Portals such as Hong Kong-based HelperChoice provide ethical benefits to employers, as well as to abused maids

BY BEH LIH YI

It was past midnight when Filipino domestic helper Genelie Millan, feeling worn out and empty, dragged herself back to her room, took out her phone to search for a way to escape her abusive Hong Kong employer, and came across the website that changed her life.

HelperChoice is one of several online services that – cutting out the middleman recruiters who charge would-be maids exorbitant fees – help such workers to avoid getting trapped in debt bondage to exploitative employers.

Since leaving her 11-year-old son in the Philippines in 2010, Millan had been forced to sleep on a sofa and hit with a pair of chopsticks before finding the site that let her choose for herself a more sympathetic boss.

“They treat me like their family. They trust me a lot,” the 39-year-old says of her new employers.

From Asia to the Middle East, thousands of migrant domestic helpers are trapped in debt and cannot escape, even if they are abused, because they have to repay the recruiters that found them work, and often make deductions from their monthly wages.

An affluent financial hub, Hong Kong is one of the biggest destinations for helpers in Asia, with some 370,000 women from the Philippines and Indonesia working in the city, according to government data. Millan borrowed 100,000 Philippine pesos (US$1,900) to pay recruiters when she moved to Hong Kong – a huge sum for a poor Filipino family.

The website of Hong Kong-based HelperChoice provides a platform for employers and helpers to connect directly, promising to help both parties find the “perfect match in an ethical way”.

For a fee starting at HK$350 (US$45), potential employers can access a database of job-seeking helpers to set up interviews. Helpers do not pay to register, while employers can choose to pay more for additional services such as having the paperwork done on their behalf.

“It’s a win-win situation,” HelperChoice’s chief executive Alexandra Golovanow says.

The website, set up in 2012, has found jobs for about 8,000 helpers, Golovanow adds, explaining that its popularity has been due in part to heightened awareness about their mistreatment. In Hong Kong, laws stipulate that recruiters cannot charge more than 10 per cent of a helper’s first month salary, but a study by campaign group Rights Exposure has shown that maids are often overcharged, sometimes as much as 25 times the legally permitted amount.

“In some cases, employment agencies also take away their passport,” Golovanow says. “Helpers just can’t leave because they have no paper, no documentation. This is modern slavery – people have no alternatives.”

Hong Kong-based Fair Employment Agency (FEA), meanwhile, works more as a traditional employment agency that allows employers and helpers to register online, and only charges the bosses for the hiring. Unlike HelperChoice, a team of staff at FEA helps match maids to employers based on criteria they have entered on their profile.

The FEA has placed 2,000 helpers since it was set up in 2014 and estimates it has saved these workers some US$3 million – money that would otherwise have gone to recruiters.

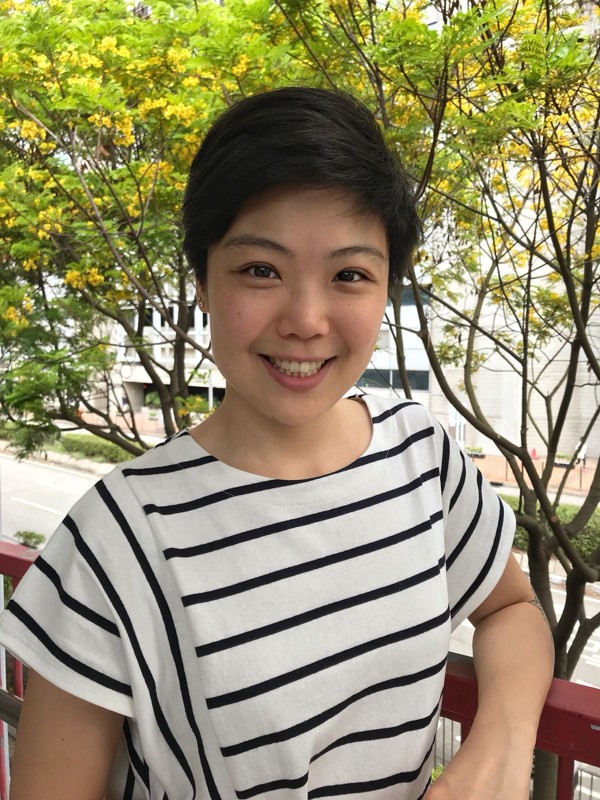

“Right now, the reason why recruitment is so mired in these unethical things is because there are too many players and no accountability,” says Victoria Ahn, from the Fair Employment Foundation, which runs the FEA project.

Victoria Ahn of Fair Employment Foundation.

Victoria Ahn of Fair Employment Foundation.

The “players” she speaks of are the many intermediaries that a worker must deal with when migrating overseas for employment. “Technology will play a huge role in clearing that up and reducing the number of players.”

FEA uses a database system and messaging tools to check in with both workers and employers after the worker begins work, Ahn adds.

“Workers are sent a text message a few weeks after they begin working to make sure that they are settling well into their jobs, making sure that they are receiving their salaries, food and proper accommodation,” she says. “Employers are concurrently sent an email to check in on how things are going, and if they have any issues they want to reach out to the agency on.”

Despite such efforts to clean up the industry, activists say the multimillion-dollar recruitment trade will continue and the Hong Kong government must step up action against unscrupulous firms.

Of about 3,000 recruitment agencies in the city, the government says that 42 were convicted between 2012 and 2017 for violating laws, but it did not specify if the convictions were related to overcharging.

“Vigorous enforcement action will be taken out against any employment agencies’ contravention to the law,” a spokesman from the Hong Kong Labour Department says via email.

Hong Kong this year introduced laws with heavier fines and three-year prison terms for recruiters overcharging helpers, and similar initiatives are also slowly making inroads in the Middle East, which is known for its notorious “kafala” sponsorship system that binds migrant workers to one employer.

The controversial system has long been criticised by activists for exploiting workers and denying them the ability to travel or change jobs without their employer’s consent.

Filipino helper Sheryl Cruz, who is based in Qatar, found out about HelperChoice through Facebook when she was searching for a job after her employer died from cancer in 2016. Reluctant to go a recruitment agency that would give her no say in who she could work for, she used the portal to connect with a Pakistani family in the Gulf kingdom looking for a helper.

“You can see all the [employers] and what they are looking for and contact them directly,” the 31-year-old says.

Cruz, who has 12 years experience as a helper, feels empowered because, for the first time, she has been able to set her own terms when negotiating for the new job – she asked for a day off and a higher wage. “I felt good setting my salary,” she says.

For Millan, HelperChoice has also been a godsend. Enjoying a Sunday break in a park in Hong Kong, she explains that living with a boss she likes is a big change, having begged a previous employer to treat her “as a person, not an animal”.

Despite all the hardship, she does not think about quitting the city and returning home.

“I always think about my son – my son’s future,” Millan says.

Thomson Reuters Foundation

(Source: scmp.com)