Artists Explore State of Filipino Art, Culture in the Diaspora

By: Wilfred Galila

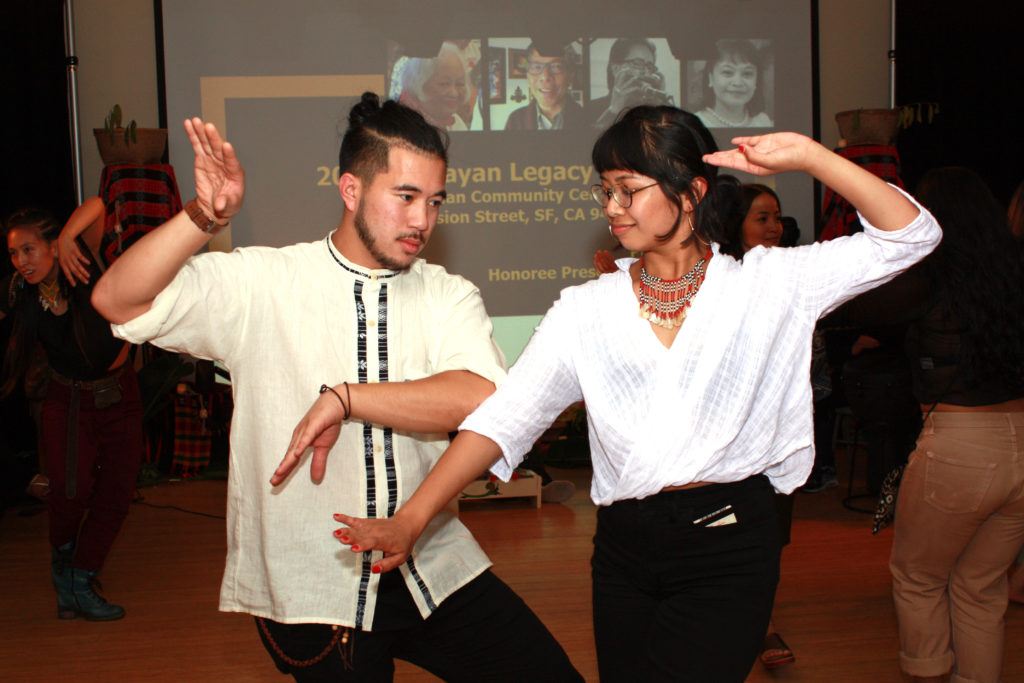

Attendees at the dance and-music workshops. INQUIRER/Wilfred Galila

SAN FRANCISCO – An unprecedented gathering of artists, cultural workers and community members on May 28 and 29 filled the Bayanihan Community Center at the heart of SoMa Pilipinas: Filipino Cultural Heritage District with artistic activity and lively explorations on the state of art in the Filipino diaspora.

The 2nd Annual Dialogue on Philippine Arts and Culture in the Diaspora is the only one of its kind in the U.S. It featured panel discussions, a performance by the Toronto-based band DATU with is brand of electronic-infused indigenous gong music and dance choreography, workshops, this year’s legacy awards and a kamayan dinner at the center’s Barangay Hall decked with Ifugao and Kalinga designs.

Kularts with American Center of Philippine Arts (ACPA), Parangal Dance Company and the Filipino American Development Foundation (FADF) hosted the two-day event.

Legacy honorees

The event recognized this year’s legacy honorees for their “invaluable contribution to Filipino American arts and culture.”

Evangeline Canonizado Buell, a multi-awarded author, musician and activist, is the president emeritus of the Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS) Easy Bay Chapter and co-chair of the Asian Pacific Advisory Council of the Oakland Museum of California. She served as co-chair of the City of Berkeley Arts Commission and president of the Berkeley Art Center. Berkeley Mayor Tom Bates and the city council honored her by proclaiming November 10 as “Evangeline Canonizado Buell Day” in the city of Berkeley.

Legacy Honorees, from left, Carlos Zialcita, Bernadette

Borja-Sy and Alan-Manalo. INQUIRER/ Wilfred Galila

Alan Manalo, director of development at Hospitality House, a progressive community center for people struggling with homelessness and poverty in the Tenderloin and Sixth Street, is a stage director, actor, stand-up comedian and a founder of “Tongue in a mood,” a Filipino American experimental comedy group that led the Pinoy invasion of Bindlestiff Studio, which today stands as the cultural center of SoMa Pilipinas.

Carlos Zialcita is a blues and jazz harmonica player, singer, bandleader and educator who has joined recordings by numerous blues artists including Johnny Otis, Sugar Pie DeSanto and Sonny Rhodes. He is a founder and director of the San Francisco Filipino American Jazz Festival, member of the board of directors of the Manilatown Heritage Foundation and an advisory board member of Philippine American Writers and Artists, Inc.

Bernadette Borja Sy, is the executive director and founder of FADF and Bayanihan Community Center. She sits on several nonprofit boards, including the Veterans Equity Center, Tenant and Owners Development Corporation, the Alexis Apartments of St. Patrick’s Parish. She oversees program activities at the Bayanihan Community Center and partners with local organizations to provide culturally appropriate resources and programming for the SF Pilipino and SoMa communities.

Art dialogue

This year’s dialogue was made up of three panels that discussed various aspects of Philippine arts and culture ranging from cultural entry points to art business, civic engagement and contemporary folk and new works in the diaspora.

The “Cultural Entry Points” panel, that identified the varieties of immersive cultural learning experiences in today’s digitally dominated world, was moderated by Lisa Juachon, a co-founder and member of Sama Sama Cooperative, a Tagalog language immersion and cultural arts summer camp cooperative for Pilipino American youth.

Panel members were: Brian Batugo, a Stockton educator and arts program director, who established the Little Manila Dance Collective and the Kulintang Academy to teach traditional dance and music to local Stockton residents; Stephanie Herrera, choreographer, cultural director and dance mistress of Kariktan Dance Company; Herna Cruz-Louie, executive director and co-founder of ACPA and the ACPA Rondalla group; Patricia Ong, dancer, arts educator and founding member of Sama Sama Cooperative; and Kimberly Requesto, lead dancer of Parangal Dance Company and apprentice to Kalinga dance master artist Jenny Bawer Young.

Herna Cruz-Louie shares her viewpoint during the

Cultural Entry Points panel. iNQUIRER/Wilfred Galila

The “Contemporary/New Folk Artists” panel discussed the ways that contemporary artists deeply trained and/or experienced in traditional Philippine art forms are defining the new folk genre. It was moderated by Lydia Neff, a performing artist and media professional, with panel members Jenny Bawer Young, a culture bearer of Kalinga traditional arts, particularly laga (back strap loom weaving), music, chants and dances; Jay Loyola, master artist of Philippine Dance, educator and founding artistic director of ACPA; Ron Quesada aka Kulintronica, a musician who fuses the kulintang with modern electronic dance music; Kristian Kabuay, an expert in the native ancient Filipino writing system, baybayin; and Eric Solano, founder and creative director of the Parangal Dance Company.

The “Art Business and Civic Engagement” panel identified essential business tools for a successful arts practice and the ways that the arts/artists are essential to civic engagement and community building and vice versa. It was moderated by Olivia Malabuyo Tablante, administrative manager and program director of the Special Awards in the Arts Program of The Wallace Alexander Gerbode Foundation, with panel members Ada Chan, regional planner for

New Diasporic Works panel members, from left, Kim

Arteche, Michael Arcega, Alexander Punzalan,

Sammay Dizon, Caroline Garcia and Aureen

Almario. KIMBERLY REQUESTO

Association of Bay Area Governments and a community development practitioner working with immigrant communities and neighborhoods in Oakland and in San Francisco; Gina Mariko Rosales, an events enthusiast, efficiency nerd, dancer, nonprofit advocate and founder of the San Francisco event production company “Make it Mariko”; Andrea Porras, arts programs specialist for the California Arts Council; Barbara Mumby Huerta, a senior program officer at the San Francisco Arts Commission; Anthem Salgado, founder and coach at the “Art of Hustle”; and Weston Teruya, a visual artist and arts administrator who has worked in civic grant making and arts policy.

The “New Diasporic Works” panel, discussed the ways that Philippine dance, music and cultural practices inform the creation of diasporic western-trained artists. It was moderated by Kim Arteche, an artist and educator who works in photography, installation and social practice, with panel members Aureen Almario, an educator, actress, writer, shadow artist and artistic director of Bindlestiff Studio; Caroline Garcia, a “culturally promiscuous,” performance maker based in Sydney, Australia who works across live performance and video; Michael Arcega, an interdisciplinary artist working primarily in sculpture and installation and an assistant professor at SF State University; Sammay Dizon, a choreographer/producer and interdisciplinary performing artist; and Alexander Punzalan, a Toronto based producer, singer, composer, multi-winning musician and co-founder of the band DATU.

Deeper conversation

“The conversation is a lot deeper this year,” says Alleluia Panis, executive and artistic director of Kularts, who conceived and helmed the two-day event. Among the “deep dive” conversations between the panelists as well as audience members was the topic of safe spaces.

“We don’t have formal spaces to always exhibit our art,” says Arteche. “With the exception of Bindlestiff Studios, we’re always pushing into larger institutions that may or may not be familiar with the contents of our work.”

“As artists, we have to take risks. We can’t get comfortable,” says Almario. “We always have to push ourselves to be in unsafe spaces. That’s what art is.”

“I’m down to not feel safe. That’s the risk we play doing cultural work,” says Punzalan. “Let’s continue to be unsafe together.”

Also discussed was the balance of playing the diversity card or sensationalizing Filipino identity for opportunity and exposure as well as the difference between creating art for audiences versus the community.

“In negotiating those spaces, I realized that I just had to give up that question altogether and make work that is for the field that I specialize in,” says Arcega whose fine art installations feature boats, in particular the Philippine bangka. “Sometimes there are strong nods to where I’m from, sometimes there’s not trace. I make work from a place where I’m just myself, I’m not trying to represent.”

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with using your ethnicity in order to get grants and opportunities,” says Garcia. “Yet we need to realize that we potentially are initializing ourselves. So I may lay down that I have Filipino ancestry, but it’s not necessarily gonna come through in what I produce.”

Contemporary New Folk Artists panel-members, from left,

Lydia Neff, Ron Quesada, Kristian Kabuay, Jay Loyola,

Jenny Bawer-Young and Eric-Solano. KIMBERLY

REQUESTO

“We have to play and recognize where we sit in the spectrum,” says Romeo Candido, producer, musician and member of DATU. “To be able to use what we can use, with being authentic and using our privileges to get what we deserve which is a seat at the table – visibility, access to funding, access to knowledge and all the other things.”

Dance and music workshop

Part of the two-day event was a set of workshops on Philippine dance and music conducted by leading practitioners in the diaspora.

A comprehensive workshop on the tagunggo gong ensemble music of the Sama, Bajau, and Tausug ethnic groups from the Sulu archipelago was led by doctor of ethnomusicology and traditional kulintang music practioner, Bernard Ellorin.

Philippine Dance master artist Jay Loyola led workshop participants through a full dance routine choreographed on the spot with the signature Loyola dance style using a vocabulary derived from folkloric dance movements across the Philippine regions.

Cultural Entry Points panel members, from left,

Brian-Batugo, Stephanie Herrera, Patricia Ong,

Herna Cruz-Louie,Lisa Juachon and Kimberly-Requesto.

INQUIRER/Wilfred Galila

Eric Solano, creative director of Parangal Dance Company, presented an introduction to the Binanog, a traditional dance that mimics the movement of the hawk or banog, learned directly from the Panay Bukidnon indigenous group of Barangay Garangan, Calinog, Iloilo.

Artists and community members gained varied experiences and awakened to a range of realizations from the dialogue.

“Coming from Australia, the community aspect of this event is the thing that speaks most to me because we don’t have that back home,” says Garcia.

Interacting with other artists in the diaspora was a validation of each other’s practices.

“From hip-hop to folk dance practice, that’s the vocabulary that’s within my body; so to know that I’m not the only one is super dope,” says interdisciplinary dancer Jonathan Mercado. “It’s definitely helping me figure out what I want to do and how to go about doing it.”

For some, the dialogue was a powerful catalyst for the resurfacing of an identity long submerged.

“I realized that this was a dialogue that I’ve been a part of already. It brought up conversations that I’ve been hushing within myself,” says dancer Alexandria Diaz Defato. “It was a really beautiful opening of this realization of the potential and spectrum of what it means to claim my roots.”

Misrepresentations

There was unanimous recognition that traditional dances created by indigenous groups in the Philippines have been given inaccurate versions staged and popularized by mainstream dance troupes such as the Bayanihan Philippine National Folk Dance Company. The misrepresentations of these dances have been mistakenly accepted as indigenously authentic. There is also a lack of attribution to the dances’ origins.

“It absolves us as creators from the critique of the work. A screen that a lot of artists hide behind.” says Panis. “Claim it, be responsible for it and stand by your work. Don’t hide behind people. Your putting it out there, then own it.”

“Honoring the dances and where they come from. Whether it’s from yourself or from an ethno linguistic group in the Philippines is most important,” says Requesto.

“It affirmed the idea I had about stating who your lineage is and the lineage of the dances that you perform,” says Peter de Guzman, artistic director of Malaya Filipino American Dance Arts in LA. “You give your respects to who you learned it from so you’re not blindly claiming that this is your dance.”

“It’s all about respecting your sources and respecting your individuality as an artist since creating something new is always a risk,” says Arellano. “It’s like moving forward in a backstroke because you don’t want to lose sight of where you came from and where exactly your sources are.”

Panis’ vision for the dialogue was a convening of various leaders of the community and diaspora, a platform where they could exchange ideas and exert influence apart from their own specific fields of practice and, ultimately, strengthen Philippine arts and culture in the community and diaspora at large.

“I feel they need the nurturing and the communication with others,” says Panis. “Having a system by which our own leaders are taking the time to really develop themselves.”

“I really didn’t even think about that, but now I get it,” says Solano. “My realization is that we can use the empowerment she’s [Panis] given us, by continuing to do what we do, continuing to learn and to work with people who are here for the future.”

(Source: Inquirer.net)